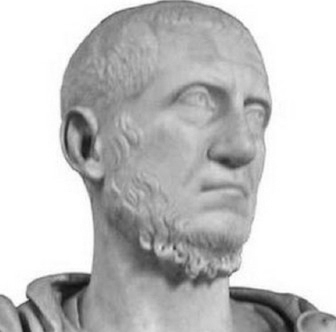

Historian Tacitus was born in 56 or 57 to an equestrian family; like many Latin authors of both the Golden and Silver Ages, he was from the provinces, probably northern Italy or Gallia Narbonensis. Tacitus was a senator and a historian of the Roman Empire.

Tacitus is considered to be one of the greatest Roman historians. He lived in what has been called the Silver Age of Latin literature. His father may have been the Cornelius Tacitus who served as procurator of Belgica and Germania; Pliny the Elder mentions that Cornelius had a son who aged rapidly, which implies an early death.

If Cornelius was his father, and since there is no mention of Tacitus suffering such a condition, it is possible that this refers to a brother. Tacitus’ dedication to Fabius Iustus in the Dialogues may indicate a connection with Spain, and his friendship with Pliny suggests origins in northern Italy.

No evidence exists, however, that Pliny’s friends from northern Italy knew Tacitus, nor do Pliny’s letters hint that the two men had a common background. From his seat in the Senate he became suffect consul in 97 during the reign of Nerva, being the first of his family to do so.

During his tenure he reached the height of his fame as an orator when he delivered the funeral oration for the famous veteran soldier Lucius Verginius Rufus. In the following year he wrote and published the Agricola and Germania, announcing the beginnings of the literary endeavors that would occupy him until his death.

Though Cornelius was the name of a noble Roman family, there is no proof that he was descended from the Roman aristocracy; provincial families often took the name of the governor who had given them Roman citizenship.

In 77 Tacitus married the daughter of Gnaeus Julius Agricola. Agricola had risen in the imperial service to the consulship, in 77 or 78, and he would later enhance his reputation as governor of Britain.

Tacitus appears to have made his own mark socially and was making much progress toward public distinction; he would obviously benefit from Agricola’s political connections.

Moving through the regular stages, he gained the quaestorship (often a responsible provincial post), probably in 81; then in 88 he attained a praetorship (a post with legal jurisdiction) and became a member of the priestly college that kept the Sibylline Books of prophecy and supervised foreign-cult practice.

During the reign of Domitian, he served as praetor, and between 89 and 93, he must have commanded a legion or governed a province. He may have been glad to be away from Rome, because the emperor and the Senate were on bad terms.

“We witnessed the extreme of servitude,” Tacitus wrote in his Agricola, [Tacitus, Agricola 2.] but that did not prevent the new senator from reaping the benefits of imperial patronage. The old war horse had been decorated for several successful campaigns in Britain.

By writing a biography of his father-in-law, Tacitus had an opportunity to make a couple of things clear about what it meant to serve a tyrannical emperor. A wealthy man had duties towards society that he could not honorably evade.

Agricola had accepted this responsibility, but it had not been easy, for example when Domitian, jealous of Agricola’s success, had decided not to prolong his governorship.